Fifty shades of... blue: The lapis lazuli

Written by Francesca Di Turo

Translated by Sarah Fortunée Tabbakh

Italian Version here

“Come then, Giovanni, try to succour my dead pictures and my fame; since foul I fare and painting is my shame.”

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Sonnet 5

|

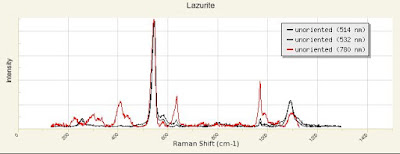

| Raman spectrum of lazurite. Credits: Ruff.info. |

When we talk about the great Florentine artist, our first thought goes to the beauty of the Sistine Chapel and its Last Judgment. The story of the execution of such a magnificent masterpiece, unique in its kind, is indisputably appealing and I suggest consulting the art history books that address the subject (see bibliography). Amongst the peculiar events regarding the realization of the fresco, one event worth mentioning is, without any doubt, the use of the lapis lazuli.

If there were a hierarchy of colours, the lapis lazuli would be the King of the Blues: it was so expensive that it was often forged or used in such a small quantity that mixing it with other pigments was necessary. The reason of its elevated cost, then as now, was not only related to its immense beauty – an intense blue unlikely reproducible by other minerals – but also to the difficulty in finding the raw material, which followed a specific trade route: the lapis lazuli route.

Let us take a look at how this colour is obtained – colour desired so strongly by Michelangelo Pope Paul III spent fortunes to satisfy the artist.

The lapis lazuli is the common name of the mineral lazurite (from the Persian “lazhward”, meaning blue) and is often found combined with other minerals (such as pyrite, phlogopite, calcite, pyroxene and various silicates). Therefore, its chemical formula is quite complex and can be synthesized as such: (Na,Ca)8[Al6 Si6 O24](Sn-, S2-, SO42-, Cl-)1-2. The lazurite can easily be found combined with the mineral Hauyna, which practically has the same chemical formula but with a high level of sulphates. You can well imagine the formation of such minerals is extremely complex, considering their chemical formula. The limestone undergoes a metamorphic and metasomatic process due to volcanic fluids, and the metamorphosis of contact occurs through the contact between magma and limestone.

The lazurite is easily recognizable in art because of the intensity of its colour. However, some scientific techniques are used to identify it, amongst which the X-ray diffraction, the optical microscope, the electron microscope, the electron microprobe and the Raman spectroscopy (What is Raman spectroscopy? Click here for more information).

In antiquity, the only sources of supply of the raw material were probably the Caves of Pamir and the Afghan cave of Sar-e-Sang, from which the above-mentioned “Lapis Lazuli Route” began. However, this cave was not easily accessible and the extraction was long and difficult, one of the main reasons the cost was so high. In a 2006 article, Ballirano and Maras (Sapienza, Università di Roma) worked on fragments of lapis lazuli from the Sistine Chapel in order to establish a hypothetical provenience of the material (see bibliography).

Before becoming the pigment we all know and admire, the lazurite had to be delicately removed of its impurities, especially the ones caused by the pyrite, which was another reason for the elevated cost of it. Then again, the lapis lazuli is extraordinarily stable with the passage of time. This is due to the complex mineralogy of the lazurite, which, belonging to the silicates category (tectosilicates subclass, feldspathoids group), makes it resistant to the most aggressive chemical attacks.

Going back to the Last Judgement of Michelangelo, the fresco technique has actually enhanced the colour and its gleam, which rarely happens when it comes to oil or tempera techniques. The story of the cleaning of this masterpiece deserves a separate post, but all I will say is that everything that had been deposited on the surface (dirt due to the passage of time, the candles, the heating, the visitors and various interactions of the surface itself with its environment) has practically left the ultramarine blue unaltered, except in some narrow spots where the ‘Ultramarine Disease’ was identified. However, this alteration remains unexplained: it is still unknown whether it is a result of an antique cleaning carried out with lye, or if the lapis lazuli was simply never used in these parts.

Today, the lapis lazuli is considered an ornamental stone, a jewel that is still very expensive. Naturally, science has managed to synthesize artificial ultramarine, conserving the aesthetic characteristics of the original lapis lazuli and lowering the cost. However, even if our means of supplying are much simpler today than the ones in Michelangelo’s times, we lack the ability to reproduce the expressive intensity the artist has given to history with his last brushstroke to the Last Judgement in 1541.

Bibliography

• P. Ballirano, A. Maras, Mineralogical characterization of the blue pigment of Michelangelo’s fresco “The Last Judgment”, American Mineralogist, Volume 91, pages 997–1005, 2006

Comments

Post a Comment